|

Humanity has been obsessed with giants and tiny people since the species evolved imagination. When we invented myth, People of Unusual Sizes populated them. When myth crossed the blurry line into fiction, we wrote them into our novels, short stories, and blog posts. When our artists figured out perspective and proportion, giants graced our cave walls, canvases, and computer screens. The history of media is the history of Size. As soon as a technology is born someone will bring capital “S” Size into it.

The first person to ever pay to see a film forked over their centimes in 1895. In August of 1901 a tiny man materialized on top of a glass of beer in “The Cheese Mites”. He was the first tiny person on film, no matter what lies Wikipedia wants to perpetuate. A few seconds later he was joined by an equally tiny couple who dragged themselves out of a bread bag. In less than a minute the tiny boys were wrestling on the tabletop while the little lady was dancing a jig.

It took another three months for cinema's first giant to take a bow. He didn't have much screen time, but the ogre in “The Magic Sword” made dramatic use of the seconds he was given, moving the plot along as easily as he carried the helpless damsel to his cave.

In-between the introduction of cinema tinies and giants made above, Vore was introduced to film in October of 1901. But that's a story for another day. It's only mentioned here for perspective. To show how quickly the new technology embraced Size. Méliès worked in Size the way Georgia O'Keefe experimented in watercolors. Gulliver and Alice made their leaps from literature to the silver screen when the 20th century was still a toddler. Since then there have been enough Size displaced film stars to fill a book.

When filling that book, an interesting gender dynamic becomes obvious. Up to a certain point women were rarely shown as being the larger character. Giants tended to be male. Tiny characters, mostly, interacted with normal-sized men. There were exceptions, but, for the most part giant women weren't a part of the cinematic Size landscape until the 50s.

Then all Hell broke loose.

Better pop psychologists than I have dissected the post-war gender dynamics at play in “The Incredible Shrinking Man”. The protagonist's diminishing role in his household reflecting mens' feelings of inadequacy in a broader world. The 50s were the heyday of Size in cinema and this film, for good or bad, is considered the epicenter of that boom in popularity.

The same ground was covered a year earlier in Norway's “Kvinnens plass”(“A Woman's Place”). A male reporter marries a female colleague. It turns out she's the better reporter. When she becomes pregnant, he decides to sacrifice his career to take care of baby and house. His difficulties dealing with life in a traditionally female role lead to him dreaming that he's reduced to the size of a child. While less subtle than “The Shrinking Man” this isn't entirely unsympathetic to the wife. The film admits that the life of a housewife isn't easy. Take out the size element and this could pass as a rough draft of the 80s film “Mr. Mom”.

But that has nothing to do with the four women alluded to in the title.

For whatever reason. Female empowerment. Male inadequacy. Outside literary influences. Or some intersection of all three. For some reason there were at least four films being peddled in mid-50s Hollywood that were titled “The Giant Woman”.

It's easy to say these were all reactions to the commercial success of “The Incredible Shrinking Man”. There are several other projects, on film and television, that got green-lit on “Shrinking Man”'s box office receipts. Some had similar proportions (“Attack of the Puppet People”, “World of Giants”); while others went the opposite route (“The Amazing Colossal Man”, “War of the Colossal Beast”). But the first of these giant women was pitched before Matheson had finished writing that book, let alone turned it into a screenplay.

Giant Woman #1: Gigantosa

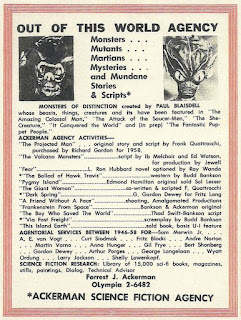

It's unclear when Frank Quattrocchi wrote “Giganturo”, but it got name-dropped in a s.f. film column in the Nov, 1955 issue of Nebula. Legendary editor/promoter/literary agent Forrest J. Ackerman (known affectionately in sci-fi circles as “The Ackermonster”) doesn't say anything about the plot, only that it was among a number of scripts that were allegedly waiting to be shot.

It wasn't until the Jan, 1956 issue of Imaginative Tales (Ackerman's “Scientifilm Marquee” articles ran across multiple s.f. magazines of the time) that any of the plot details were made public.

It gives me great pleasure, therefore, to report the talents of s.f. author Frank Quattrocchi, who does know something about s.f. and does definitely care for the medium, have been employed to produce an original sci-fi screenplay! Quattrocchi, who has authored such memorable yarns as “Assignment in the Unknown,” “The Addict,” “Sword from the Stars.” etc., has been commissioned to write, and had been accepted for immediate filming, a 109 page shooting script about a radioactive island of giant mutations. S.F. artist and special effects man Paul Blaisdell has already been called in for a consultation by the producer's design department. Color and widescreen treatment are contemplated for the Quattrocchi film.

Fans of 50s sci-fi/horror might recognize the plot synopsis. Change the location from an island to an isolated Mexican valley and you have “The Cyclops”. That film came out in '57, but was probably filmed in late 1955. Ackerman would've had the connections to know about it, but it's unclear if Quattrocchi had heard any details. Conspicuously absent from this pitch is a giant human of any kind let alone a lady goliath. Without a big person, this sounds like another of a long line of “land of the dinosaur” type films that stretch back to the silent era.

More tidbits were dropped in other Ackerman columns throughout '56. It's explicitly stated that “Gigantoso” and “Giganturo” are different names the film was being shopped under. The giant woman plot point first gets mentioned here:

A natural for a double bill should be Frank Quattrocchi's original screenplay GIGANTOSO (about a radioactive island of mutated giant animal life, including an Amazonian giantess) and THE SHRINKING MAN by Richard Matheson. A fine five figure sum has been reported for Dick to transmute his own as yet unpublished Gold Medal novel into screen form for Universal Studios.

An article from '57 defines the unnamed Amazon (I took some liberties calling her Gigantosa) as being three men high in her “stalking feet”. Compared to the two miles “The Nth Man” was supposed to achieve. “Nth Man” was eventually shaved down to “The Amazing Colossal Man” proportions when Bert I Gordon took over productions

By '58 the title had been reworked into “The Giant Woman”. Ackerman suggested it was only a small rewrite away from being a perfect sequel to “Colossal Man”. Elsewhere he claimed it was being shot in Mexico in color. An ad for Ackerman's agency that came out in '58 claimed the scripts was co-written by Quattrocchi and an unnamed collaborator. The same ad mentioned another Quattrochi script (“The Projected Man”) was sold to Richard Gordon in '58.

Whatever title it was peddled under, “The Giant Woman” was Ackerman's girlfriend from Canada. After all the hype and effort, not a single frame of film was shot. If a script existed (and I think it did), it was either too bad to use or would have been too expensive to make for the film companies Ackerman had contacts with. AIP probably got a look at it and passed. As did Richard Gordon. As of this writing it is nothing more than an obscure footnote to extremely niche genre of film.

Frank Quattrocchi would eventually get the screenwriting credit he was searching for. The script Ackerman claimed to have sold in '58 made it to screen in '66. It wasn't the most successful of films. Or one that cinema historians hold up as a stunning example of the craft. But “The Projected Man” got made. And that's more than you can say for most film pitches.

Giant Woman 2: Gigante

Speaking of unmade film pitches.

Giant women may have been a novelty on film in the first half of the 20th century, but the movies weren't the only pop culture game in town. Serious science fiction literature of the time tended to avoid Size, but the pulps were another matter. Put together cheap and published fast, the pulp magazines of the day had a voracious need for stories and a paucity of people who were both capable of writing at a professional level and willing to stoop to working for the low rates most pulps paid.

To say that anything went would be a gross oversimplification. But it is safe to say that creators had more artistic freedom in the pulps than they did on film. In print, it didn't cost anything more to make your protagonist 100 feet tall than it did six feet. Or six inches. Same with the cover art and illustrations. To make those scales work with live actors wasn't cheap. If a story didn't go over well in Thrilling Wonder Stories, the editor might be out a penny a word; if an expensive feature film bombed, careers were ended.

Our next giant woman could have stepped out of the pulps and onto the screen. If she ever made it that far. In fact, an argument could be made that she was, I'll be kind and say, inspired by a magazine that would have been on the shelves at the time of her creation.

Gigante is a hot mess of a film pitch. That's her name, by the way. Because “she has to have one” according to her character description. The pitch itself is called simply “The Giant Woman”. It's twelve pages read like what you'd expect if the crew at Mad Men's Sterling Cooper were asked to come up with a giant lady story. Salacious, but censored. Misogynistic or empowering. Representative or racist. Maybe it was earnest. Maybe it was a joke. Both interpretations are on the table given what we have to go on.

It's impossible to make a direct comparison with the previously discussed giant woman, Gigante, and the two who are to follow. The latter two actually made it to screen. The first may have made it to script, but if that script still exists I haven't been able to find it.

At least a handful of “The Giant Woman” pitch documents are floating around out there. As of this writing there is one copy for sale through a reputable online bookseller. I purchased a different copy from another reliable source. Each is twelve yellow typewritten pages giving an overview of the characters, plot, and some sample dialog. The sort of thing short enough to whet a studio executive's appetite. If any bit, it would get turned over to the scriptwriters.

Quattrochhi had a full script I haven't read. Beck and Birdwell had a synopsis I can overanalyze. Quattrocchi's script was publicly hawked in media I could track down almost 70 years after the fact. If Gigante was discussed it was behind closed studio doors. Probably not kindly.

The original story idea was written by George Beck and Russel Birdwell and dated May 28, 1957. About a month after “The Incredible Shrinking Man”'s first box office receipts were counted.

Beck, a founding member of The Writer's Guild of America West and an active member of The Director's Guild, was mostly known as a writer. He wrote and directed the Shelley Winters/Farley Granger vehicle “Behave Yourself!” in 1951, wrote the story that “Take A Letter, Darling”(1942) was based on, and had a steady stream of television writing credits through the 50s into the 60s. He wrote for Lassie and Dobie Gillis; Blondie and The Thin Man.

Birdwell began his Hollywood career as a publicist for “The Son of The Sheik” in 1926. He worked PR for some extremely well respected films including “Gone With The Wind”, the 1937 version of “A Star Is Born”, “Rebecca”, and “Monsieur Verdoux”. Like Beck he wrote and directed as well. He has more directing credits than Beck, but fewer writing. His biggest claim to fame is writing the 1951 biopic “Jim Thorpe – All-American”.

|

| No Size content here, folks. Just another Hollywood whitewash. |

It's unclear when these two met or if they collaborated on any other film pitches. Neither had even a whiff of sci-fi in their resume.

But you didn't come to read about them. Back to the giant woman.

“We'll call her GIGANTE since she must have a name.” opens the pitch before going on to describe her thusly:

To picture her, think of Ester Williams; now think of Anita Ekberg. Think of them both – physically. Then, after turning them both slowly over (in your mind, of course) dwell on the most luscious attributes lavished on each by a bountiful Nature. Now sort those attributes according to preference and make yourself a composite WOMAN. Take that result and multiply IT by about twenty. Now you have Gigante. She's something over a hundred feet tall, and most ALL of that vast loveliness is quoted practically verbatim under the skimpy animal skins she, being feminine to the ultimatest ult, has managed to piece together into a garment of sorts. The face is oriental in cast – magnificent almond-shaped eyes; high brow and cheek bones; a complexion of honey-amber and black-black hair to her knees.

It may be saying something about my age, but when I read WOMAN in all caps like that I hear it in Animal's (from “The Muppet Show”) voice. If you know the character now you are too.

You're welcome.

It's clear they're pushing the sex appeal as far as they could in 1950s Hollywood with this Frankenstein lady, made up of the best parts of real life sex symbols. Esther Williams, the noted swimmer-turned-actress, was known for her shapely legs (and by extension, backside). Ekberg was getting billed as “Paramount's Marilyn Monroe” around this time since she was a.) blonde, b.) busty, and c.) publicity people aren't always that imaginative. William's career was still going strong, but probably slightly past her peak. Ekberg had fewer film credits than Williams at that time, but her social life and pin-up career (including a Playboy appearance a few months earlier) would have been enough to put her on Beck and Birdwell's radar.

|

| In case anyone doubted it, Esther got back. |

As to Gigante's race.

On the one hand, she's found in the Himalayas so it would make sense that she's non-caucasian. On the other, a couple sentences later they suggest she might be the “sole survivor of the Neanderthal Race”. Which makes sense if you think neanderthals were dinosaur sized, and don't mind insinuating that “orientals” are significantly less evolved than white people.

Of course it was 1957; even if they had filmed this they'd have cast a white actress. Maybe hispanic. Censors at the time gave less scrutiny to skimpy costumes if they were worn by “savages”. It wouldn't be the first time Hollywood had cast a woman of the wrong color to wear yellowface.

The next most important character is Tom Hutton. Beck and Birdwell spend almost as much time describing how mercenary Tom is as they do insinuating Gigante's assets. Personally I think they dropped the neanderthal in the wrong bio; if anyone reads as cave-man in their character description, it's Tom. All women are “broads” to him and he makes crappy jokes about them. He's a fighter pilot, deep sea diver, gun runner, and “an assortment of other storied, soldier-of-fortune roles. It is quite likely that Tom Hutton is the last mercenary extant.” He allegedly doesn't have a sentimental cell in his body.

He's been hired to guide a rescue mission into the “unmapped unknown” to find some lost explorers connected to the vaguely named “American Museum”. Seems that somewhere in his soldier-of-fortune past he had to skydive into that unknown. A year later he made it back to “room service and bottled bourbon”. The Museum figures if he can find his way out once on his own, he can do it again, faster with help.

That help consists of Dean Gardner, an older explorer who heads the expedition, Dr. Samuel Wilson, a medical man who has been on a few of these adventures before, and the natives who do all the real work and actually know enough about the unknown to leave it the heck alone.

The rest of the named cast consists of Jonathan H. Bentley. A tycoon's tycoon who builds empires at the drop of a hat and his daughter Donna.

Donna Bentley – who has everything she ever wanted and to whom it is inconceivable that she'd ever want anything she couldn't have – until she meets and wants Tom who regards her as just another broad. Like Gigante, only littler. But, still a broad.

The story starts six weeks into the expedition. Gardner's convinced they're one mountain away from either the survivors of the previous expedition or evidence of their demise. Tom's been having trouble with the native guides. There've penetrated pretty far into tabu lands and there are whispers if they go further, none of them will come back.

Naturally Tom cajoles and threatens them until they tow the line.

Our hero, ladies and gentlemen.

Dr. Sam falls into a snow crater and calls for help. It's a good thing Tom and Gardner get there ahead of the natives; the locals would freak seeing a human footprint nine feet deep, big enough to fit six men.

They tell themselves some lies about it being a weird happenstance and remind themselves not to tell the natives. No need to bother them about something when it might inconvenience the white men. Tom can only cajole so much.

The next day Tom leads a group of eight natives to scout the route ahead. The going it treacherous. The nine have to dig out foot and hand holds in a sheer rock face so the others can make the trip carrying equipment and supplies. Instead of the sherpas taking point, we have Tom in front. Cause he's the hero, this is 50s Hollywood, and that's the way God wanted it.

The nine men are tied together as they make their through “several really frightening moment” suspended over “sheer nothingness, over three miles of nothingness.” At one point Tom has to make a leap to continue his ascent. I don't want this to devolve into snark, but I like to think that when the sherpas below applauded it was the kind of supportive praise you give a kid who's done good. Anyone of them could have done it better, but doggone it, you did it.

Tom loosens his rope and slips it around a convenient boulder. The first sherpa [note: they are never referred to as sherpas in the treatment; I'm using the term to be slightly more accurate and to drive home the fact that these people are highly skilled at what they do] climbs after Tom. Halfway up he stops and screams at what he sees above.

Whatever it is, we know it's impressive; even Tom's eyes bug out at the sight.

The first evidence of the title character was her footprint; our first sight of Gigante is her hand.

An incredibly huge hand thrusts out of a crevasse in the mountain and between its thumb and forefinger, almost daintily plucks the rope. The men hug the cliff face, trying to get into the stone. They scream in abject, insane terror. Suddenly men and rope are yanked away and are held dangling over the abyss. They look for all the world like as many beads on a string. The rope seems the sheerest spider's thread and the men trapped flies as the hand jounces the thread. But all are tied about the waist, so are not torn loose. All but Tom. He had loosened his end to anchor the rope. At the third jounce he flies off into space and plummets down, down, down. An instant before he must splatter against the rocky floor, the hand swoops lazily and plucks him out of thin air. Tom grabs wildly, embracing the middle finger which is about as long as he is tall and as big around as himself.

I've been more than a little critical of the treatment up to this point, but that would've made a good scene. Filmed right there would have been action, dramatic tension, and an introduction of our main character that doesn't rely on showing off her figure. I can picture it vividly with stuntmen on a rope in a process shot with the actress's hand pulling a string before cutting to a a giant hand prop when she gives Tom the middle finger.

A giant hand prop was used in “Dr. Cyclops”, but I think Beck and Birdwell probably had a daintier version of King Kong's hand in mind when they pictured this. This whole pitch reads like a gender-flipped Kong with Tom as the (relatively) tiny ape.

The sherpas vanish because their mothers didn't raise idiots, leaving Gardner and Dr. Sam to look for Tom. We pick up with the two white dudes holing up somewhere vague on the side of the mountain resigned to die without the help of the sherpas.

Whatever they are hiding in (the treatment doesn't say) somehow keeps them from noticing Gigante has scooped them up “as if by some huge mechanical shovel, and are riding through space.” The viewer gets to see Tom riding that giant hand like a mahout directing an elephant. That's the term they use, “mahout”. The sherpas were “native guides”, but they at least got that right.

It's implied that the men are unconscious at this point. Which makes not noticing getting shoveled up by a hundred foot woman more plausible. When they come to they are in “a cave of almost infinite immensity”.

We're told that Tom has developed a rapport with their captor. We catch a glimpse of it when he elephant-rides her. If they had made this film I hope they would have shown more of that development. I don't want to keep going back to Kong, but part of what made that movie work were the scenes of him and Fay Wray's character bonding.

Now that Gigante is introduced we get another description of her to hammer home the sex appeal.

… a giantess. But a giant giantess. Over a hundred feet tall, perfectly proportioned and mother-naked under animal skins she has contrived into a garment of sorts.

I sussed out “mother-naked” from context, but did some digging to confirm. Essentially it was another term for wearing your birthday suit; being as naked as the day that you were born. From what I can tell this was probably old fashioned when they wrote it back in '57.

As to being naked under your clothes? Technically, we all are, but I'm going to suggest they were trying to say she wasn't wearing underwear under her loincloth. It may just be me, but the description makes me think of Jane in some of the pre-code Tarzan movies. When she got into animal skins they were cut to show a lot of thigh and almost all of her leg except a small string of fabric connecting the front and back. You could tell she was going commando as well as native.

|

| Maureen O'Sullivan as Jane in all her pre-Code glory. |

Despite not having a sentimental cell in his body Tom says she's a really nice kid. He's teaching her to speak English.

Again, I'd rather see at least a little bit of that. Maybe even have him learn a little of her language.

In a corner of her cave is what's left of the expedition Tom and pals came there to find. Blanched skeletons and a crate marked AMERICAN MUSEUM – NEW YORK. It's unclear if Gigante had anything to do with their deaths or if she found them that way and brought them home to be bric-a-brac. The fact they've only been missing a year and are now skeletons suggests they got eaten. I'm not an expert, but I don't think exposure to the elements in a cold environment would lead to skeletons that fast.

Gardner and Dr. Sam come up with the brilliant idea of bringing Gigante back. This is the first time her name is actually said out loud and it's explicitly stated that they are the ones who came up with it.

Tom forgets he's a mercenary without a cell of sentiment for a little bit and refuses to go along with their plan. “He can't see subjecting this big, beautiful broad to any circusy exhibition. Let her alone. Leave her where she belongs.”

A big enough bribe reminds Tom who he really is.

The next trick is getting Gigante to a port where she can be transported to the US. Simple. Unlike giant monsters in other films she's not only sweet on the human love interest, but she understands English and takes orders. She carries them out of the Himalayas in a pouch at her waist.

Act Two skips the boring parts and gets us straight to New York. And by “boring” I mean the parts the writers didn't want to think about. Mongolia is bordered by Russia and China. Neither of whom are that friendly with us now, let alone during the peak of the Cold War.

Personally, I'd love to see what they pulled out of their butts to get through that one. And the reaction from either country's military when they saw a giant Asian woman carrying three capitalist pigs in her purse. I'd pay good money to see that movie.

Geopolitics aside, the nearest ports would've been Pacific. Guess what isn't on the Pacific? New York. To get to Hawaii would've taken over a month, maybe two depending on the departure port and speed of the ship. Which couldn't be that fast since it had to hold a 100 foot person and enough to feed her till they could hit the nearest supply stop a month later.

Yeah, I know; I should really just relax.

Instead of all that we open Act Two with newspaper headlines in many languages proclaiming Gigante's arrival and a montage of steps taken to accommodate a woman of her proportions. The biggest ballroom of the Waldorf is now her bedroom. Her bed “acres of foam-rubber mattresses, stacked a dozen deep on the floor.” Miles of sheets and blankets are sewn together to make her bedding. They turn the hotel swimming pool into a bubble bath.

Fans of gowns will be pleased to know they would be featured in this film.

It takes the combined facilities of several of the most swanky Fifth Avenue coutourieres to make a gown for Gigante. Hordes of Lilliputian seamstresses, on ladders and scaffolds, drape that gorgeous body with bolt after bolt of silk and satin, pinning here, tucking there – all under the screamed directions of the head designer over a public address system.

Meanwhile, in Nevada, Glenn Manning is looking at his adjustable man-diaper and wondering what sin a man could commit to deserve that fashion disaster.

I actually like this scene. And not for the salaciousness. Censors of the day would've kept things from getting too risque and it shifts the movie slightly out of the typical sci-fi/horror into romantic comedy territory where makeovers are as inevitable as death and taxes.

It also, arguably, shows a serious break from the Kong narrative. At this point in his film Kong was getting wrapped in chains, not silks and satins. Gigante came to this country peacefully and she is being treated kindly. She's being exploited every bit as much as Kong, but she has a nicer cage.

It's also possible to read the gown as another form of bondage, that Kong's chains are more honest, but the beauty standards being imposed on Gigante are every bit as constraining.

I'm sure none of that was going through Beck or Birdwell's head when they came up with it; they just wanted their giant WOMAN to be well dressed when she rampaged.

Somewhere in all this Tom isn't happy at the way things are going down. Gigante's being exploited every bit as much as he knew she would and he still hasn't been paid.

He shows up in need of a shave at a party thrown by the Bentleys (in need of a shave cause he's that kind of fella) to drop some exposition. We are told Jonathan sponsored the trip back after a long call from Gardner and Dr. Sam. Tom's bribe was confirmed, but he was told he wouldn't be paid until Gigante (called cargo) arrived in New York.

We do find out the port they leave from was on the North China coast and that they were taken away on Bentley's largest luxury liner. It's unclear how long the three men and a giant lady had to cool their heels in China, but Bentley had to send it there. Unless it was in Japan it might have added another couple months to the voyage home.

I almost agree with Tom being so angry; six months between the bribe and payoff is wrong. And not paying once he's there? That's just bad form.

Bentley's richer than Croesus, but can't afford to let Tom be on his way. Gigante has become so attached to the little guy she'll follow him if he tries to skip town. We're told he tried it before and Gigante wrecked havoc as she looked for him.

Skipping a month's long sea voyage is one thing; when action scenes become exposition you're doing something wrong. I know you're trying to keep the budget reasonable, but there's a better way.

This wouldn't be a gender-flipped “King Kong” without a normal-sized love interest to complete the triangle. We know from her character description that Donna wants Tom and we finally get to see that. Donna (and her father) are used to being obeyed. Her reaction to Tom:

Donna Bentley is more than somewhat taken with Tom's independence. He's something entirely new to her and his apparent disinterest in her as a woman piques her more than she will ever admit, or abide. The fact that Tom is at all concerned about Gigante and what will happen to her in all this hullabaloo is a source of amusement to Donna. How can he feel anything at all for that monstrosity? Tom bridles: Gigante is a dame like any other, even Donna herself, except bigger. She's got feelings like any other broad. He doesn't want any part of this and never did. He feels like a heel for wanting out now –but the damage is done and he wants his dough. Yes, indeed – Tom is something very different to Donna. She decides he's about the most necessary ingredient she needs to attain the fuller life.

In rom coms Donna is the fiancee who gets dumped when the guy figures out that what he wants is the girl who isn't rich or perfect, but is right for him.

Know who isn't rich or perfect? Gigante. But this isn't a rom com.

By this tine Madison Square Garden (or an armory in case the budget won't stretch) has been turned into a medical theater. In a part of her initial character description we were promised “she will be explained in incredulously gasped detail by learned doctors and scientists riding up her towering length on hydraulic platforms to hold stethoscopes and other scientific impedimenta against that creamy bosom to listen to the thunder (on track) of that great heart”.

The line is repeated almost verbatim at this point in the pitch. Sadly the authors were so focused on that creamy bosom to come up with any real explanation of Gigante's size. The throwaway line about maybe being the last neanderthal in her character bio is the closest we get to science. And that's not very close.

Personally, I'd love to see one of these 50s scientists shrug their shoulders and mumble they're clueless. There's so much we don't understand in the real world, so many mysteries it took teams of scientists around the globe decades to suss out. Just once couldn't the (at best) handful of experts who get called into these movies be stumped?

But people don't like that. There has to be a cause for all the bad things that happen. Steps we can avoid gaining a fly head, growing 60 feet, or sprouting fur when the moon is full and the wolfsbane blooms. It's very reassuring to know there's always a man in a white coat who can tell us what went wrong; make sure it couldn't happen to us.

As a kid watching these movies I never bought that. Every terrible thing in them was fair game to come after me or be done to me. The monsters were real; the reassurances were the lie.

I'm not surprised the treatment doesn't include any technobabble hand waving. It doesn't seem like it's the strength of the writers and not what they were concerned about. Stephen King once wrote that having nuclear waste be the origin of the pickle-eating frog monsters in “Horror of Party Beach” wasn't a message against nuclear dumping; the producers wanted pickle-eating frog monsters and atomic energy was the excuse they pulled out of a hat.

Beck and Birdwell wanted a 100 foot woman, who cared about the excuse.

And I don't fault them for that.

Gigante's heart is unhappy. Tom's been spending less time with her and when he does show up he's with Donna. And he leaves with Donna. Gigante may not have had much human contact before, but she's got a pretty good idea of what goes on when Tom and Donna aren't with her. Gigante puts up with all this circus BS and the doctors clucking and perving on her for Tom's sake. Why should she put up with that humiliation if Tom's going to neglect her for that other woman?

Things come to a head when Gigante tries to confess her feelings for Tom. She demands Donna be sent away so only Tom gets to hear what's in her heart.

Donna laughs at that.

I don't blame Gigante for trying to grab Donna; she had it coming.

Tom manages to keep the peace and get Gigante settled down. She “subsides, pouting like a scolded child.” It's not the first time the treatment refers to Gigante as being childlike. It's one of the things about the character that keeps me thinking of Kong. That and the being gigantic.

Tom goes straight from Gigante's side to Bentley's penthouse. This time Bentley gives in to Tom's demands for payment. Tom takes a taxi to the airport and hops a plane for Europe.

The third act does not go well for New York City.

There's only so long Gigante will stay calm without seeing Tom. Five seconds after that and she's on a Tom hunt up Broadway and down Fifth Avenue, kicking anything on wheels out of her way like so many toy trucks, and staring through high-rise windows like a peeping Tom on stilts.

It's not in the treatment, but I'd like to see the “giant monster looks through window at pretty woman” trope get flipped if anyone ever does film this. We've seen women in negligees, bathtubs, and boudoirs over the decades; it's only fair they show a guy struggling to cover his junk while a giant set of lady eyes leers through the blinds.

The treatment describes the military force being rallied to fight the giant WOMAN. I've seen enough of these films to picture the stock footage of tanks on the march and planes being launched. The tally is one squadron of fighter jets, one tank regiment, and two regiments of infantry. Not enough for D-Day; this is more a DD-Day.

I know. I'm ashamed of myself too.

Gardner, who hasn't been mentioned since Act One gets on an airfield loudspeaker and pleads with Tom to come back and fix the mess they made of things. Why he didn't have the tower radio the plane isn't clear, but it does make for an interesting scene. Though, again, we're veering a bit into rom-com territory. Not that that's a bad thing.

Tom “comes running, hoping poor Gigante isn't destroyed before he gets to her.”

Like Bentley warned him would happen if he left.

Someone … gives Gigante directions to the Bentley place? I don't know. The outline says Gigante has figured out where “that woman Donna” is; I can see her shaking the information out of someone.

However Gigante knows it doesn't take her long to get to an adjoining building and start smashing through windows and walls with her huge mitt until she finally seizes Donna.

Actually it reads “sizes Donna”, which is now my favorite typo ever.

Donna conveniently faints so she doesn't have to hear Tom sweet talk Gigante down from her rampage. Things will be different this time. He'll spend all his time with her. Even go back to Mongolia if that'll make her happy.

But Gigante prefers it here. A hundred mattress bed at the Waldorf is better than a cave with skeletons for décor.

But the guys with the guns show up and don't see it that way. Gigante is too dangerous to be housed among civilized people. Something has to be done. Won't anyone think of the children. Tom tries to reason with them, but they aren't listening.

Gigante ends up chained in an armory. The treatment says it's like Gulliver, but it's hard not to think of Kong. According to Beck and Birdwell it took half the army to put her there. Tom convinces her to go home, that they'll destroy her if she stays there.

There's an escape and a desperate run to the waterfront down at The Battery. He points the way and she creates a tidal wave as she gets in and “with three strokes surges past Sandy Hook.”

The last glimpse Tom has of her is when she rises waist high in the sea to wave a final, wistful farewell – then her back and haunches as she submerges – and swims beyond the horizon.

The named characters mill around the dock watching all this. Tom gets out one last “broad”. Donna is woman enough to admit she's probably responsible for most of it even though she had nothing to do with Gigante getting lured away from her home.

Donna apologizes. Tom shrugs and walks away. Donna has her chauffeur stalk after him with her in the backseat.

The end.

-----

There are multiple copies of “The Giant Woman” available through a number of reputable booksellers. Almost certainly more in private collections. A number of sellers draw attention to it by making a connection to a film that was actually made and will be discussed in detail later in the third part , “The Attack of the 50 Foot Woman”. The seller I bought my copy from strongly suggested this as well in their online listing, but balked when I asked for specifics.

The case for “The Giant Woman” being rewritten into Attack isn't strong. There's a giant WOMAN in each. They're both in love triangles that don't end well for anyone involved. Attack was originally announced as “The Astounding Giant Woman”. They both feature a scene where a giant hand comes crashing through a window to get the other woman.

That's about it.

It's not like Beck and Birdwell's treatment was the first giant WOMAN ever; sure as hell not the first tragic love triangle. A giant hand reaching through a window to grab a pretty woman goes back to Kong groping for Fay Wray over 30 years before. The original title is a natural progression from “The Incredible Shrinking Man” and “The Amazing Colossal Man”.

Attack's poster art might be questioned. I wouldn't be the first to point out that the now iconic image (a giant woman bestride an elevated highway in a major metropolitan area) is nowhere close to anything we see in the finished film. Or that the woman casually tossing cars was much bigger than 50 feet. Gigante (who was closer to the scale of the lady in Attack's poster) went on a rampage through New York City, while Allison Hayes took a pissed-off saunter through some unincorporated desert. If I had to match the poster art to the project, I know which film I'd attribute it to.

It's possible the producer's of Attack got a copy of “The Giant Woman” but they didn't have the budget to make such an ambitious picture. There's no indication they were even interested in this sort of movie until after “The Amazing Colossal Man” turned a profit. Months after the pitch was written. They even hired that film's scriptwriter (Mark Hanna) to write Attack.

Hanna's autobiography doesn't mention anything about him being given a story outline. I don't think he was. At least I haven't come across any smoking guns.

When I first saw this pitch document I thought it might be a fake. One, because it had never made it onto my pop culture radar. Two, because it conjured up images of a 100 foot tall Anita Ekberg – five years before she would play one in “Boccoccio '70”. If anything, the giant woman in that Italian film seems closer to Gigante (post makeover) than Allison Hayes in Attack.

|

| Ekberg as giant. |

For a number of reasons I do think the Beck/Birdwell treatment is legitimate. But the conspiracy theorist in me can't help but notice the Woolner's had connections with the Italian film industry. There's no direct link between the Woolner's and Fellini, but I can't help but wonder if (and this is a huge “if”) they passed along the idea for giant Ekberg to someone in his camp.

It's interesting to note that this pitch wasn't the only time a pre-Boccoccio Anita Ekberg was imagined as a giant. Ackerman (yeah, the same one who promoted “Gigantosa”) made an offhand joke in one of his articles suggesting Ekberg would make a better lead for what would become “Attack of the 50 Foot Woman”. It's very likely he would have known about the Beck/Birdwell pitch. Whether he was thinking about B&B's pitch or if Ekberg was the first woman to spring to mind when the subject of bust size came up is anybody's guess.

|

| In case anyone doubted Ekberg's credentials. |

A million years ago, before I beat the similarities between Kong and Gigante into a dead horse, I dropped some vague allegations about Gigante being inspired by the pulps. I haven't come across anything that would suggest that either Beck or Birdwell had read much science fiction. Pulp or otherwise. But there are some covers out there that bear some strong resemblance to what we saw in their pitch.

The cover to “Queen of the Ice Men” (Fantastic Adventures, Nov. 1949) bears a strong resemblance to what we're given in the pre-NYC parts of Giant Woman. The Ice Men takes place at the Arctic Circle instead of the Himalayas, but the visual of a giant woman in furs towering over failed mountaineers is almost identical. Though the title character in the novel isn't as “mother naked” on the cover as Gigante is described. The story itself is also pretty far removed from what Beck/Birdwell give us. In this, our giant woman is the head of a society who can grow to giant size at will. The romantic shenanigans that go on aren't worth commenting on. They're a trope, not a coincidence.

“Tonight The Sky Will Fall”'s (Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy May, 1952) cover gives us a visual closer to Gigante's final rampage. A beautiful woman in an evening gown tearing through the streets of a major city. Probably New York. The cover has next to nothing to do with the story inside, but I'm sure it sold more copies than a text-accurate one would have.

The October, 1954 issue of the same magazine would feature another giant lady dressed to the nines. Although Toffee is clearly being playful instead of outright destructive. She's also much smaller than the lady on the '52 cover.

More of a stretch would be “The Incubi of Parallel X” (Planet Stories Sep, 1951) or “The Sea People” (Amazing Stories Aug, 1946). The giant women in the former are green skinned with exaggerated arching brows. The sort of fetishized “exotic” that might be translated into real world women of color back in the day. Echoes of that sort of thing were being played off in Star Trek 15 years later. Depending on your views of Gamora and Mantis in the MCU, they may still be with us today.

The latter with its topless giant (nipples discretely hidden by her and an admirer's hands) standing in the waves matches the censored sexuality Beck and Birdwell played with. Unlike “The Giant Woman”, this lady is facing towards the viewer instead of swimming away from them. Her expression more “come hither” than goodbye.

The strongest (although still circumstantial) connection between the pulps and “The Giant Woman” is the March 1957 issue of Fantastic Science Fiction,“The Goddess of World 21”. The title is followed by the tagline “Hated By Women – Preyed On By Men”. Unlike the other titles, it was on the stands only a couple months before the pitch was dated. It's easy to picture one or both of the writers picking up a copy, thumbing through it, and making up their own story based on the visuals and a few snippets of text.

The similarities are there on the surface, but disappear when you actually read the story. The sort of legal protection old school Hollywood types would have loved. The giant woman standing akimbo on the cover matches Gigante's scale and dress sense, but that's about it. She's attractive, but hardly the Franken-pinup B&B conjure up. Her hair isn't as long as their creation. And it's brown, not black. And she's caucasian. Take away her height, put her in a nice dress, and the goddess of world 21 could be the girl next door.

The goddess on the inside of the book is another story. Virgil Finlay based his interior illustration of the title character on Bettie Page, lifting a three year old image of her posing in a bikini. He changed the way she was looking, upped her cup size, and added a tiny man on her right boob.

Take away the space suit, and the little man could be one of the doctors checking out Gigante's heart rate. Have your characters call her Asian and 50s Hollywood would be happy with the casting. It's not defensible, but I can see it happening.

That's Gigante.

Mix the cover tagline with the plot of King Kong and you have “The Giant Woman”.

-----

Could this have been a good movie?

Probably not. At least there are too many “ifs” to give a meaningful answer. If it had a solid script (not written by B&B). If it had a decent budget. And a good director with the right technical people. If the cast had chemistry. It would take a perfect storm of creative talents to turn the 12 page pitch into something good.

But it's not impossible. Some of the basic tropes at play are solid. There are some good ideas. Even if they were included accidentally. If this had been made in the 50s it might have made a good vehicle for Page herself. If they came up with a reason why the giant foreign lady was white. Page had wanted to get into films. Salacious as this was, “The Giant Woman” still would've been a step up from the cheesecake photos and fetish porn that paid her bills back in the day.

Maybe one day someone will work with the estates of Beck and Birdwell to make this film. Either as the type of film they had originally envisioned or as a commentary on modern society and it's treatment of women. Both have their merits. Neither would be easy. As one of the few people who have a copy, I'm not holding my breath waiting for Spielberg to call to borrow my copy.

Comments

Post a Comment